A BITTER HISTORY

Bitters have been having a moment for a while now. For the past couple of years we’ve seen the rediscovery and resurgence of these alluring liquids in bars around the world. Technically there are two types of bitters: Amaro, Italian for bitter, is what your grandparents would receive after, or possibly at the start of, a meal and can be drunk straight. Thought to aid with digestion, not all aperitifs and digestifs are bitters, but many are. Amaro are extracts of different types of plant material, (like herbs, roots, bark or fruit) mixed with water to dilute the alcohol strength. Aromatic bitters share similar ingredients, but are more like pure extracts, where a drop or two goes a long way. They generally have a higher alcohol content, are less diluted, and are not drunk straight, but added to a cocktail or water as a flavor enhancer. Starting with trendy bespoke cocktail bars and working their way down to the local dive, you can now get a solid negroni at most places, but where did they come from?

The earliest evidence of bitters being added to alcohol was found in a vessel that held wine, buried in a tomb dating back to 3150 B.C.E. Egyptians likely added either terebinth or pine tree resin to wine to take advantage of its antioxidant properties. It is also likely they added herbs to wine, although difficult to pinpoint exactly which ones with certainty, because the compounds found in the vessels containing the wine are shared across ten herb genera, although only three of these are thought to have been found growing in the area when the wine was made. It is probable that tree resins were also added to fermented beverages as early as the Neolithic period in China, but not provable because of the environmental degradation. It is also probable that around 3000 B.C.E. they were adding herbs to wine in Spain and beer in Europe, but not yet proven with as much evidence as the previously mentioned Egyptian wine.

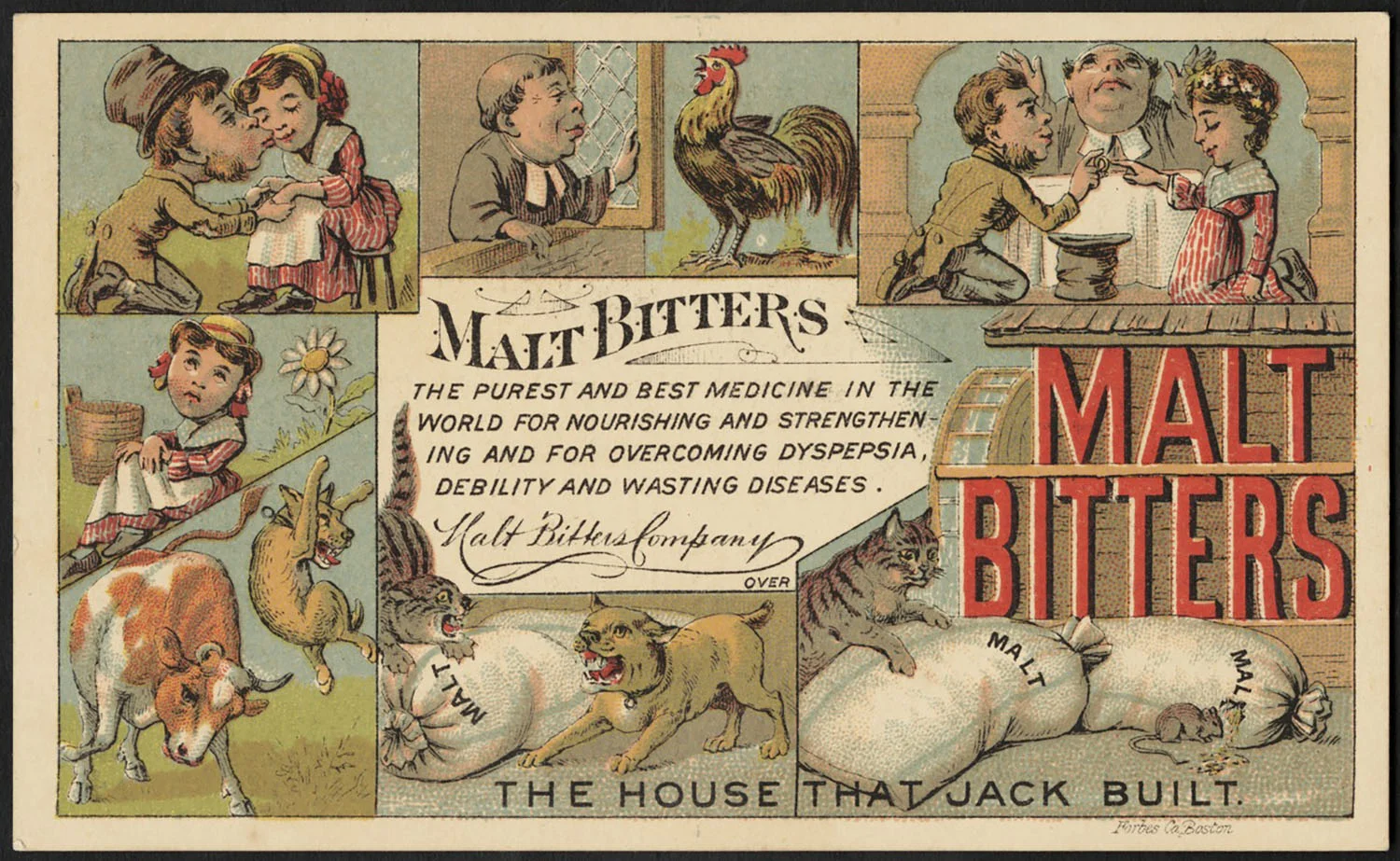

Drinking bitters before or after meals to aid in digestion is first referenced sometime in the 5th Century by Greek theologian St. Diadochos of Photik, who believed that people wishing to “discipline the sexual organs” should avoid drinking aperitifs, “presumably because they open a way to the stomach for the vast meal which is to follow.” Skipping forward quite a bit to the 17th Century, bitters started being identified with patent medicine. Named after the “letters patent” given by English royalty, patent medicine was a catch all term for over-the-counter medicine. The letters patent worked in the same way a patent works today, where the manufacturer was given a monopoly over the formula; although today medicinal patents generally only last for a certain amount of time, and then after they expire other companies are allowed to manufacture their own version. Bitters were believed to have medicinal properties and were consumed either as a shot or diluted into a glass of water, not mixed into alcohol.

Sometime in the 18th century, people in England were mixing bitters into Canary wine to help cure hangovers, and by the early 1800’s bitters were being used to cure or prevent all types of ailments, from malaria to headaches. Both aperitifs and digestifs came into vogue in the late 19th Century in Europe, as people coming back from military tours of Africa had grown accustomed to drinking them while abroad to prevent illness, both straight and mixed into drinks. The first definition of the word cocktail, published in the May 13th, 1806 edition of the newspaper The Balance, and Columbian Repository, mentions bitters as one of the ingredients necessary, although at the time cocktail wasn’t the catch all term for alcoholic drinks it is today and meant a more specific type of mixed drink.

The temperance movement really changed the use of bitters in everyday life. Even though they had a high alcohol content, bitters were typically classified as a food product, and therefore allowed to be drunk during prohibition. This became a bit of a double edged sword for the companies that made bitters, because while they were legally allowed to sell them, they had become commonly mixed into alcohol and therefore most widely used by bartenders. In combination with the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which shut down many small makers of bitters, when the bartenders disappeared so did many of the remaining brands. While even strict teetotalers accepted the use of bitters for medicinal purposes, average people stopped using them unless to add to poor quality homebrewed or bootlegged drinks to bring up the alcohol content. After the repeal of the Volstead Act in December of 1933, the damage had already been done.

Bitters began to make their way back across the Atlantic in the 1970s with the resurgence of the cocktail, but the palate of the era skewed towards sweet and generally only called for a bar to be stocked with one or two types for cocktails and a few digestifs and aperitifs if they also served food. Even as recently as 2004 there were only three brands of commercial aromatic bitters around. No one can say for sure what caused the popularity of bitters to come back, it's possible the reason was the changing palate, which has been turning towards more bitter flavors in the past ten or so years. Or maybe it is the renewed interest in small batch, local food goods that allowed space for smaller companies to flourish.

-Heather Clark

TEQUILA OLD FASHIONED

1 1/2 ounces tequila blanco, such as Espolón

3/4 ounces mezcal, such as Del Maguey Vida

1 dash Bittercube Jamaican #2 bitters

1 dash Bittercube orange bitters

1 peel blood orange, for garnish

In a cocktail shaker filled with ice, combine tequila, mezcal and bitters. Cover and shake until condensation forms, about 20 seconds. Strain into a chilled Old Fashioned glass filled with ice and garnish with blood orange peel.

-Cocktail by Tommy Werner